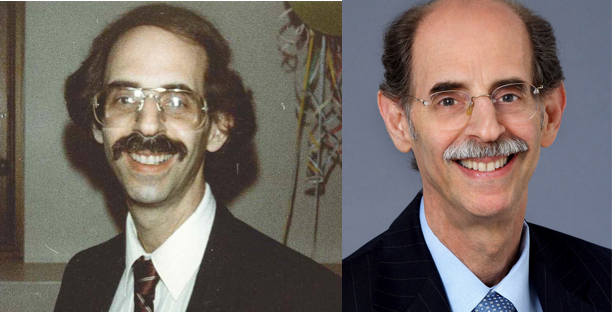

Director of Pediatrics at Bellevue Hospital, Dr. Dreyer is President-elect of the AAP and an active member of the APA, having served on numerous committees and councils in both organizations, including past President of the AAP’s New York State Chapter 3 and as National President of the APA. Dr. Dreyer has worked extensively on issues of health literacy and child poverty, and is currently collaborating with members of the AAP and APA to push policies promoting the health and safety of children in poverty at the state and national level.

Why did you choose pediatrics, specifically pediatrics at Bellevue?

I’ve always loved children, and so I went to medical school to become a pediatrician. That was my goal when I went to medical school, and I didn’t change my mind, and I haven’t been unhappy about my decision. I came to Bellevue really to devote my career to taking care of poor children and their families, and trying to improve the care that they get. Even my research has been focused on how we can help improve the early childhood development of poor children. Clinically, I’ve always taken care of poor families, I’ve always wanted to take care of poor families, and so my advocacy has stemmed from my experiences with these families.

How did you become involved with the AAP’s current strategic priority of child poverty?

I gave my speech at the end of my president year [as APA president], and I decided I would speak on childhood poverty. That started a lot of advocacy, and I’ve been dealing with childhood poverty from then on. Number one, I learned a lot about childhood poverty; I knew the experiences of my patients, so I knew about poverty, but I didn’t really study it. Literally I read everything there was, and got very involved in what the policies were in this country and other countries about childhood poverty in preparation for my speech. But then out of that speech there was a real desire out of a lot of people to continue this and make this a pediatric issue. The first thing that I’ve done is I’m now the head of an APA taskforce on childhood poverty, it has many people on it, we have lots of projects. Then out of that, the AAP president-elect reached out to me and said, “I really want to work with you on this.”

So at the AAP big meeting, which is called the NCE (National Conference and Exhibition), I was meeting with people and trying to get the leadership–the presidents, the people on the strategic planning committee to adopt it. And I did a good enough job doing that (and also I think they’re good people, I don’t think it was all me),that they responded to this. I’ve been so impressed by how much the pediatric community has responded to this. It’s like the “aha” moment. So the Strategic Planning Committee met in November and agreed to propose to the board that they adopt child poverty as their next strategic priority. And at the end of that meeting, they voted yes, they would adopt childhood poverty. That meant that as of [Summer 2013], that became one of the strategic priorities, and they’re meeting about it.

How is the AAP moving this strategic priority forward?

The president and the president-elect of the AAP have been working very collaboratively with myself and with the current president of the APA to politic in Washington about this. So our advocacy is both at a federal level and a state level. The federal advocacy involves trying to get to a variety of government agencies who have programs for kids to see if they can improve what they’re already doing, so I’ve already been with colleagues, both from the AAP and the APA, to meetings in Washington to meet with federal agencies, including the ACF (Agency for Children and Families), and MCHB (Maternal Child Health Bureau), primarily those two agencies, but also the Department of Education, to say, “well here we are, pediatrics, we care about poor families, these are our ideas, we want to work with you.” We’ve also reached out to the President’s office. The President has something called the Domestic Policy Council–they receive instructions from him to develop policies, and they also feed him information. They’re sort of a conduit–one conduit–to getting to the President’s office for policy.

You’ve also worked on the issue of health literacy within the AAP. How did you get involved in this?

I submitted a resolution through the chapter and district that I was involved in already to the national process on health literacy. We should be developing things on a lower literacy level so that poor families can read them; they should be in multiple languages, because we have so many patients that speak other languages. That resolution went to the big resolution meeting that’s held every spring and got picked as one of the top ten resolutions, and that means that the AAP has to do something about that. So they appointed me co-chair of this health literacy project advisory committee, which worked for about four or five years on improving health literacy within the AAP. One of our projects was a national conference, another project was a book–we had various kinds of projects we were working on through that process. Out of that, I got appointed to the National Institute of Medicine’s roundtable on health literacy. So one thing leads to another.

What is one of the biggest challenges you face in your work?

Advocacy is a marathon–it’s not a sprint. Don’t expect today you’re going to make a difference. You may hit your head against a wall for five years, and then one day you’re really going to have a breakthrough on a really important issue. Or you may be lucky, and try to get some small wins, or big wins or whatever, but advocacy is mostly incremental, and mostly over the long haul, not over the short haul. So the lesson is, if you want to do an advocacy project and feel good about success in three months, it’s probably not going to happen. You’re beginning to develop skills, learning about issues around how to go about doing things, and at some point, in the future, you might actually accomplish something.

How can people become more involved in advocacy?

If you want to be involved, you can be involved. It’s not that people are trying to keep you out. I belong to two major volunteer organizations–I don’t get paid for that. So one of the major issues for me has been how to carve out the time to do this. And that means that I do a lot of work off schedule. But the satisfaction is that when you accomplish things that are good for people and children, you feel you’ve really made a difference. It also keeps you grounded in your day job, where you might be frustrated that you’re not doing what you want to do, or more importantly that you’re not accomplishing for families what you want to accomplish, but then at a higher level, you are doing something. For me, the other thing about advocacy, at this level, it’s an amazing growth for you–you’re growing, your skills are growing, you’re meeting all sorts of people, I mean, it’s fun, but it’s a new, mind-expanding experience.

ONE YEAR LATER: What progress has the AAP made with the strategic priority of child poverty?

We’re in the process of prioritizing how we sort of begin this very ambitious agenda. In the interim, we’re really supporting at the advocacy level universal preschool and minimum wage increases across the country; we’ve been fighting food stamp cuts; we’re now actually getting involved with the border children (unaccompanied children crossing the Texas and Arizona borders), trying to advocate for them to protect them from being deported without a fair hearing. In New York locally, we now have a grant through the chapter to focus on young children living in homeless shelters.

The other thing the AAP is trying to do is build partnerships with other organizations. There’s an organization called Too Small to Fail, which is supported by the Clinton Foundation, and the AAP is working with them on a lot of issues in early childhood for poor kids. There’s also a new policy on early literacy, basically supporting programs like Reach Out and Read. They’re also reaching out to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, which has just come out with a new commission statement saying that what we need to do is focus on poor kids in early childhood, poor neighborhoods to get better, and really focusing on the social determinants of health. We can’t do this by ourselves.

I never would have thought that we would be where we are today, even a year ago. I’m not necessarily optimistic about solving the problems of poor families, but I am very optimistic about the response of the pediatric community, and the amount of advocacy that is going on. And we just need to keep it going–so far I’ve been very impressed by this overwhelming response from all parts of the pediatric community.